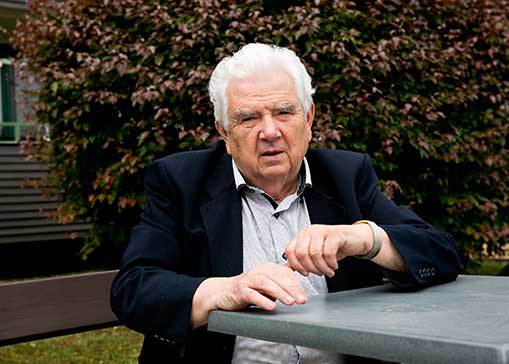

Looking at the daily schedule of Zdeněk Pololáník, one cannot tell that he will be eighty in October. Just last Sunday, he performed at a mass in the morning, inspected the performance of his opera Noc plná světla: transparent none repeat scroll in Olomouc in the afternoon and played at a concert in Besední dům in Brno in the evening. His music is well known to concert visitors and movie fans; some of his songs are sung at churches. This year’s Brno Organ Festival is devoted to his jubilee. We met in the village of Ostrovačice where he works and plays the organ at the local church.

You are a graduate of a school of music where you majored in the organ. You have something in common with Olivier Messiaen, Petr Eben or Anton Bruckner. Do you feel any inner harmony with them?

Not at all. I prefer Romantic music and I have never had any role models. During my studies I was in contact with the work of many authors from A to Z and their most famous works, but it did not motivate me in choosing my own path. They did influence me, of course, because one must have certain foundations. The influence was not one-directional; there was the tertian harmony followed by the quartal harmony or various –isms. I have memorised only a handful of really good things which have caught my attention. It was more subconscious than it was conscious. I have been doing this ever since. Everytime anyone would try to find a system in this, they would fail. There is no system, intentional or not.

How does an organ affect a composer? Does it offer anything specific or does it limit them in any way?

How does an organ affect a composer? Does it offer anything specific or does it limit them in any way?

I liked organ because of the colourfulness and variability of its sounds. It is an instrument that changes with time and its environment, with the style of churches. It offers numerous possibilities. As a student of a school of music I took an extra major in addition to the organ and I was given a task consisting in the composition for two instruments. I did not choose two one-voice instruments; instead, I chose organ and piano, so that there would be as many tones and colours as possible. Initially, my teacher did not want to approve this project but eventually the piece was successful and attracted some attention. It opened the doors to Czech Radio and to artists: the pianists Vlastimil Lejsek and Věra Lejsková and the organist Miloslav Buček asked me for a piece for two pianos and one organ. And I wrote it for them. I am interested in sound colours and the organ offers the greatest variety of them. Sure, there are synthesizers but their sound is way too artificial.

The opening concert of the Brno Organ Festival in the Jesuit church will be devoted to your jubilee. How do you like the “new organ for Brno”?

I am really happy about it. I am glad the local organists embraced it immediately and that its concerts are popular. Hana Bartošová is not only a vigorous organist but also an organiser. At the same time she is not competitive towards other organists and she invites superb performers. The new organ offers new opportunities. It enjoys real fame after years of neglect, even though their purpose was to attract people to the church.

What are they going to be playing for you? Have you composed anything for this purpose?

What are they going to be playing for you? Have you composed anything for this purpose?

Mrs. Bartošová and her daughter will play my new piece – a transcription of one of my earlier pieces for strings and piano. I arranged it for the organ and piano, the latter of which is rarely heard in our church. The programme will end with a piece for a choir – I offered several of them and I don’t even know which one got selected.

Ten years ago an organ festival in Česká Třebová was named after you. What was your initial reaction to this offer?

It was nice to be noticed. More importantly, the director of the festival František Preisler is concerned with publishing contemporary sacred music. He used to visit me at Petrov where I was the resident organist; he would sing chorals with us and he was interested in my work, because I was hard at work on my own projects even before 1989. I used to compose for liturgy, songs with Biblical topics, and in 1970 I even wrote the Song of the Songs for a large choir, orchestra and soloists. It is a two-hour oratorio on a Hebrew text and it could even be staged. I am still waiting for it to be staged, so that I can see it firsthand. Evald Schorm was interested in the Song of the Songs; he envisioned a play in an outdoor theatre. Unfortunately he did not live long enough for the time to be right to stage this. However, he did invite me to Laterna magika, for which I wrote a ballet piece named Sněhová královna (The Snow Queen). The conductor Ondřej Pipek, the then-director of the Macedonian National Theatre in Skopje, wanted to stage the Song of the Songs in Dubrovnik – with cypress trees around, just like in the libretto. We kept correspondence back and forth and he wrote that I did not even know what I had composed. However, he was not allowed to leave Yugoslavia and I was not allowed to travel there.

In the 1960’s you were a member of Tvůrčí skupina A whose members also included the composers Jan Novák, Alois Piňos, Josef Berg and Miloslav Ištvan – very different types of composers indeed. What was the force that kept you together?

In the 1960’s you were a member of Tvůrčí skupina A whose members also included the composers Jan Novák, Alois Piňos, Josef Berg and Miloslav Ištvan – very different types of composers indeed. What was the force that kept you together?

It was an attempt to prove that you cannot command artists as if they were soldiers. The fact that we were all different allowed us to do music our own way. Even Berg addressed this issue in a sad interview given a few days before his death. He said that it was not our goal to fulfil the criteria of any - ism , be it an eastern or western style. Our goal was to show the variability in art and the individualism of our work. Jan Novák based his work on Neoclassicism, as he had worked with, and was naturally influenced by, Bohuslav Martinů. I never really wanted to be a modernist. I did my own music that was appreciated by performers and listeners. Piňos and his pupils created team works which were more rational than they were emotional. And Ištvan was a one-of-a-kind individual.

One of your teachers at Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts was Theodor Schaefer who, at least according to Jiří Beneš, was extremely pedantic. Is it true that it scarred you forever?

The first time I met him was during my senior year. My previous mentor was Professor Vilém Petrželka. He told me to file a request that he be my mentor for the rest of the year, but the request was denied and I was assigned to professor Schaefer. I remembered him from the secondary school of music. He was pedantic but we got along very well. When he found out about the request, suddenly the two were on bad terms. Luckily back then I had some of my pieces performed in the Soviet Union. Here, I was accused by Ctirad Kohoutek for playing clerical music but at the same time my music was highly appreciated in Leningrad. It was good for Theodor Schaefer to have a student like me and the year with him was great. I was invited to a panel discussion at the conservatory in Leningrad. I went in spite of the ministry’s ban. The Soviets put their foot down and I had many friends there from that time on. It was important because the regime had to give me a break because my music was played in the Soviet Union.

How did your music get to Russia, anyway?

How did your music get to Russia, anyway?

It all started with a class at the Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts; my music was played in class and students commented on it. The class was attended by directors of various schools of music from the Soviet Union; Jiřina Kolmanová performed piano preludes for me. The piece caught aroused interest and I was offered correspondence with students of Soviet schools of music. They included Sergei Slonimskiy or Boris Tischenko, Oleg Janchenko and many others. During the summer break I copied several pieces and sent them to the students. Instead of just reading them, they organised an entire concert. It took place on 28 September. This day is important to me for two reasons: it is the St. Wenceslas’ Day and the day my mom died. A press release was issued the very next day and it got all the way to Czechoslovakia via the Czechoslovak News Agency. I was about to be expelled from the school. During the senior year the school asked the local municipal authority in Ostrovačice for a personality assessment. The reply said that I played the organ at church on a daily basis and that I was not a member of the youth movement or any other political organisation and that I did not fulfil the desired profile of the proper citizen of the socialist state. The assessment scared the people at JAMU. When Theodor Schaefer was about to announce my departure from the school, he said we should at least make a list of my pieces and venues where they were played. I said “They were played in Leningrad”. That was the defining moment.

Your opera Noc plná světla (Night Full of Light) had its premiere two years ago. It was based on the legendary Paul Claudel and it addressed the issue of salvation, sacrifice, conciliation and redemption. Is it fair to say it is the ideological and spiritual high point of your career? Perhaps a Parsifal of sorts?

Yes, we can say that. It is a very strong topic. I started to work on it, as scenic music, together with Zdeněk Kaloč shortly after the Velvet Revolution. Claudel was a new element.

On the other hand, your first opera was a 1966 comedy Funus bláznů (Funeral of Fools). It seems totally different from your serious spiritual agenda…

On the other hand, your first opera was a 1966 comedy Funus bláznů (Funeral of Fools). It seems totally different from your serious spiritual agenda…

This topic was offered to me by Václav Renč. But when you think about it, it is also a very strong and deep topic. The leading character is convinced that he is dead. He lets people fool him because they act as if he had died. One cries, one plays a bishop who is supposed to officiate the funeral. He wakes up from his dream just as he is about to be buried. It was a very strong topic back then. Burying somebody alive and convincing them to think they had actually died was like taking somebody’s existence for ideological reasons. People would attend trade union meetings and vote for the dismissal of their colleague and then they would speak to him in private and say “you have to understand, I have a wife and kids”. But he too had a wife and kids. But when Václav Renč died the project remained unfinished.

Are your most often staged pieces also your most favourite? Or is there any piece that would deserve much more attention?

I treat all my pieces equally, be they children’s songs, songs in hymnals or a full-length pieces. Of course I have a thing for the most recent pieces, just like families cherish their youngest the most.

You have composed, and you continue to compose, scores for movies and theatre. Do you take this work as serious as you take your concert pieces? Do you ever use a piece from a movie for your string quarter and vice versa?

You have composed, and you continue to compose, scores for movies and theatre. Do you take this work as serious as you take your concert pieces? Do you ever use a piece from a movie for your string quarter and vice versa?

I do take this work just as seriously. Sometimes you simply have to ignore your ambitions and put the topic before music. Sometimes I would compose for brass bands, sometimes it would be jazz or folklore. I also did some Russian-sounding music for Russian-themed pieces, such as Eugen Onegin or Boris Godunov, or Spanish music for Lorca. It is inevitable. If a character’s name is Juan or Rosalinda there is no room for Japanese five-tone music.

You are the author of the score for the movie Lev s bílou hřívou. What was it like to compose the score for a film about Leoš Janáček?

It was necessary to include some of his style elements, while maintaining my own style. The director chose me because he felt it would be appropriate to have the composer for a movie about Janáček from Brno. I refused at first but Jireš told me “You live in his city, where he lived and worked and his pupils were your teachers. Who else should do it?”

Do you ever visit a church were your oratorio is just being sung? Or have you ever had an unexpected encounter with your own music?

Do you ever visit a church were your oratorio is just being sung? Or have you ever had an unexpected encounter with your own music?

I rarely go outside because I am still the organist in the church in Ostrovačice. I am there on every holiday. However, I was on a vacation once, we lived in a private residence and the landlord told me that there was a Czech miniseries (Synové a dcery Jakuba Skláře) on TV and invited me to watch with them. Coincidentally, the miniseries featured my score, so I told him I knew the programme very well.

Zdeněk Pololáník (b. 25 October 1935 in Brno)– composer, organist and educator. Author of approximately 300 individual opuses – he composes operas, ballets, oratorios and symphonic and chamber music. He also composes music for theatre and film; he composed the score for the TV series Synové a dcery Jakuba skláře (1985, Dietl) and Gottwald (1986, Sokolovský), or movies such as Žert (1968, Kundera– Jireš), Nikola Šuhaj loupežník (1977, Sokolovský), Opera ve vinici (1981, Jireš), Neúplné zatmění (1982, Jireš), Katapult (1983, Páral – Jireš), Člověk proti zkáze (1989, Skalský, Pleskot) and many more.

No comment added yet..