The first impulse for the interview with the basso Richard Novák was this year’s Easter Festival of Sacred Music. We started and finished the interview with it. Try talking about this year with a man who has been a singer for sixty years. Richard Novák will be 83 this year but he still has it. And if based on the following words he may sound a bit conceited, be aware he is telling it like it is.

I am looking at your portrait above the door. Who painted it?

Cyril Klimeš, you probably don’t know who he was. He was an excellent pianist, a teacher at the conservatory. He is 88, I think. We had many concerts and recording sessions together back in the day. He was multitalented – sculpting, crafts, anything. He would build you a quasi Renaissance cabinet using just hand tools. He would build an arched ceiling in a cellar which every contractor would tell you it is not possible. He was a perfectionist. I wasn’t sitting for the portrait, though. When I came to Brno, Pepan Berg asked me to review a series of pieces he had recently composed, because it was complicated. I didn’t feel competent enough but he knew I was a musician and that he would recommend a pianist. He sent me to Cyril Klimeš. I came to his studio; we hadn’t met before. And he just took the sheet music and played it perfectly. He would not like the modern ways of doing music because he never let anything out unless it was perfect. For example Schumann’s Liederkreis or Schubert’s Schwanengesang required thirty rehearsal sessions. He would require one do-over after another, saying he must temperate and hear me. I was lucky to have met a man who had plenty of time to do it properly… which you don’t get much these days. Today you have a hard time finding a pianist for two rehearsals.

You are saying that people are not as thorough as they used to be?

When it comes to things I know well, I am sure they can be done. Or if the singer is a half-genius. For example Ivan Klánský does not need more than two rehearsal sessions – sometimes one. Other than that, it is more challenging.

When was the first time you performed at the Easter Festival of Sacred Music? Do you remember the early years of the festival?

When was the first time you performed at the Easter Festival of Sacred Music? Do you remember the early years of the festival?

I didn’t pay much attention. Or maybe I was at the Easter festival without realising where I was. It was Petr Fiala’s project and I was not “his man for the job”.

I found your name in the programme from 1997 in Haydn’s The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross. But I cannot remember when was the first time I saw you perform. It was definitely in the early 1970’s… probably in Liška Bystrouška and you played the hunter…

Liška Bystrouška was performed in 1965 on the occasion of the grand opening of the Janáček Theatre, and I played the vicar. I played the hunter in the version from 1970.

I saw that one. I was too young for the first one in Janáček Theatre.

That one was Wasserbauer’s. Back then I had some complaints regarding the stage setting. It would seem okay today, but back then it seemed overly technical and not poetic enough. But when you see how terribly some things are produced, you have to admit its quality was as good as possible. It is a well known thing that it is extremely complicated to recreate a forest on the stage. A huge backdrop photo is impossible these days. And other solutions are far from satisfactory. The forest simply has to be there because all the animals live in it, so you cannot have some universal setting. When I saw the last production of Liška Bystrouška – without my involvement – I was hugely disappointed.

I didn’t like it either, it seemed too dark.

And the chickens were weird and the pub was in the back yard of the forester’s lodge… it was a weird mix.

In 2001 you won the Thálie award for lifetime achievement and in 2005 the award of the Minister of Culture for the contribution to the world of music. What do these awards mean to you, to the audiences or to the media? Are they good at all?

In 2001 you won the Thálie award for lifetime achievement and in 2005 the award of the Minister of Culture for the contribution to the world of music. What do these awards mean to you, to the audiences or to the media? Are they good at all?

I don’t think they are that important. The number of award shows keeps growing. Everybody has an award and the value of being an award winner is not that high. During the First Czechoslovak Republic there were just the state awards which are similar to the Ministry of Culture award. I think I should be proud of myself for these achievements. On the other hand, I cannot forget what Jiří Suchý once told me. He won the Thálie award in the same year as me; we even shared a dressing room. I told him “Do you know we are almost exactly the same age?” He was born on the 1st of October; I was born on the 2nd. And he said “Once you have reached a certain age, the people giving these awards don’t really know who should be next. So they give them to the old generation because they are not expected to do anything stupid to be stripped of the honours. But please, even if I do anything stupid, do not take this award away from me”. I think this world needs its awards. Let’s take the Český lev award. There is the Best Actor, Best Actress, Leading Role, Supporting Role, Music, Production et cetera… When I got the call that I won, they asked me not to talk about it just yet. So I kept it to myself but it got me thinking “Why did they give the award to me, singers from Brno rarely get it. It may be because I am old (I was seventy) and they thought they would give it to me so that I can finally quit and make room for the younger generation”.

Lately I have you associated mostly with Bohuslav Martinů. In his opera The Greek Passion you played both priests – Grigoris and Fotis – and eventually even the role of an old man who asks to be buried in the foundations of a new village.

Lately I have you associated mostly with Bohuslav Martinů. In his opera The Greek Passion you played both priests – Grigoris and Fotis – and eventually even the role of an old man who asks to be buried in the foundations of a new village.

But this was not a Brno production. This particular show was produced as a joint project between Bregenz and Covent Garden, as an exclusive guest performance.

What was it like, knowing one opera left to right and right to left?

The supporting role was most difficult. It was in English, which was torture for me because I had to memorise the lines and I was already relatively old back then. I have to admit I suffered quite a lot. On the other hand, my ambition is to turn this small supporting role into something bigger and more significant. I was partly inspired by Karel Berman who played this old man in a Prague production that I saw. I was really moved by Karel’s performance: even though the old man has only two shorter segments, Karel was very genuine and convincing. So I said to myself I had to try it too.

And you succeeded. I was able to recall this role as I was preparing for this interview. I did not even have to look it up. Your casting in a similar role in Bohuslav Martinů’s Julietta is symptomatic...

Yes, but there was one more part of an old man played by Vlastík Šíma. He was a buffo bas, a very talented and spontaneous type of an actor. He spent many years in Brno; he remembered Janáček’s first premieres.

You only went to a school of music after your graduation from high school. Your mentor was Jiří Wooth.

You only went to a school of music after your graduation from high school. Your mentor was Jiří Wooth.

I have his self-portrait over there, very authentic. He was a trained singer, very similar to Cyril Klimeš. He was also very good at handicrafts; he could make enamelled jewellery or sew a man’s jacket – he didn’t go to any trade school, he just figured it out. After graduation he joined the army and he was assigned to the Frýdek garrison. He met his wife in Frýdek; she was a catch because his father in law had a factory. And since they could afford it, he and his wife went on a holiday in Italy in 1937, I think. He could sing and play the piano. He even took lessons from Otakar Ševčík in Písek. He was a tenorino, so he went to Čedok and asked them to recommend a place in Italy where he could take singing lessons. They told him to go to Pesaro which was famous for the Rossini conservatory, with its teacher Arturo Melocchi, and beaches too. So he went and they returned the year after because Melocchi told him it would take years. And then WWII started, so they stayed in Italy, he was taking lessons from Melocchi for a few years and worked as a renovator of paintings. When he returned he was hired by the conservatory and I was among his first students. After graduation I joined the seminary which was shut down and all students were forced to enlist and joined the special forced labour units. Jura Holeňa and I managed to succeed on the admission tests to the conservatory. I was a student of Wooth’s for only two years. It was a lot of work. He then joined the ensemble of the theatre in Ostrava. The department was shut down anyway as a result of some inspection visit from the Ministry of Education from Prague. They evaluated the curriculum and said that it was all wrong, and that was the end. I was lucky because I was pretty good in theory and harmony…

…that’s very unusual in singers, I would say.

Right. But Professor Theodor Schaefer who taught the harmony seminars came to me and said “You know what? A new department of composition will open in fall, starting with juniors. Everybody will have to have two years of a certain instrument and then they can transfer to the composition department, I will be the head of the department. Do you want to apply?” And I said I did so I escaped singing. So technically speaking I am an amateur when it comes to signing because I did not graduate. I got stuck with the “incorrect method” and it has stayed with me to this day.

I heard Theodor Schaefer was a pedantic educator as well. One in a long line of your pedantic teachers…

I heard Theodor Schaefer was a pedantic educator as well. One in a long line of your pedantic teachers…

He was a very reclusive teacher of composing, but he was also very systematic. Harmony was taught four hours a week, two two-hour blocks. That was enough to actually learn something. He said “I know that one-half of this class has had no introduction to music theory, so we will focus on it during the first semester and then we can proceed to harmony”. And he was indeed very pedantic. We had calligraphy which included the shading of half notes. He taught us where bars and stems are drawn. I still remember the rules. He taught us scales and sharps. I think it was very useful because when we started with harmony, we already had this background. His teaching method was based on Otakar Šín, i.e. functional symbols. T is tonic, D is dominant, the third pitch was crossed TD and the sixth pitch was diagonally crossed ST, which was really smart. You don’t say just pitch, you also know that it is an incomplete subdominant, or it is a secondary dominant, so it made sense. I was pretty good at it and he would always ask me to stand at the blackboard, he would play the notes at the piano and I would draw. His typical homework was two examples and whoever would have parallel fifths and octaves would always get a C-. He was strict. Nowadays it is an anachronism.

I would not say it is an anachronism. I think students want to avoid it as much as possible… and they do. It is taught at the Department of Musicology, after all.

Yes, but they are expected to go back in history and learn something about general bass. But I am not sure a modern composer even cares about this.

I think it is individual. As for the theory, do you study the entire sheet music or just your role?

We would not get sheet music. The archives featured parts and we would receive piano excerpts which was good for ensembles. But definitely not the entire score.

Basically your entire career is associated with Brno and its opera, didn’t you want to work elsewhere, especially abroad? Have you had any offers? Your skills would be put to good use anywhere…

Basically your entire career is associated with Brno and its opera, didn’t you want to work elsewhere, especially abroad? Have you had any offers? Your skills would be put to good use anywhere…

I have not had any offers, to be exact. In 1968 we were in Germany and I was seriously considering emigration. I think we were in Trier and we also visited Saarbrücken and they told me they would love to have me there but it would have to be right away. It would have been perfect because I would not have had to think about existence. And then we went to Lübeck where I spoke to Bernhard Klee who was very nice to me and said “You don’t have to explain anything, I came from the Eastern Bloc, too”. But my wife told me she would do it but her mom would never forgive us. So we stayed here but I don’t think anything serious happened.

Jaromír Nečas told me some time ago that your cousin, the composer Jan Novák, really hated the communists and he eventually did leave the country. How did you feel about it?

I think his case was a bit different. On the one hand, he was very sensitive, friendly and outgoing. On the other hand he truly hated communists and he would have gone to prison sooner or later, had he not left for good. He would have had to provoke them. He couldn’t have cared less about the oppression. He was happy he pissed them off and when they kicked him out from the union of composers he didn’t mind. It was not easy to leave but it wouldn’t have been good for him to stay.

According to Alena Veselá you are the only person who can nail his Passer Catulli.

It’s hard to tell. I was used to these styles. In the 1960’s when Skupina A existed, various outlandish things were composed and I would always sing these roles because nobody else wanted to do it. Most opera singers…

…hate doing new things.

Yes. Zbyněk Vostřák was my hardest task ever. He used to compose placid music, even ballets. But then he went serial, he founded Musica Viva and composed three sonnets inspired by Shakespeare. And he asked me to sing them. He told me straight away that Karel Berman would always do it but after a year of studying he gave it back and said he couldn’t make anything out of it. And he added “Give it to the Novák fellow in Brno, he’ll do it”. I really wanted to nail it because I practiced every day with the piano. It was really hard in terms of rhythm and intonation. Plus it was in English. I sought help and one English teacher told me I couldn’t learn anything in three weeks if I had never learned English. And I told her “No, here is a microphone, you can record it for me, I will come back next week”. And then I would just listen to it over and over. I came back next week and she was surprised how big progress I had made. So I told her “Okay, I will recite it now and you will stop me whenever I make a mistake”. So eventually I made it. I think if somebody has a talent for music, they will hear the details in the language. Last year I did Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius in Ostrava; also in English. I had two excellent recordings – one with Rattle and one with Britten. So I had to listen to them over and over, it was a lot of hard work. They did the same piece in Dresden with Kreuzchor and a basso from England who had to fill in for René Pappe. The conductor told me he did not notice any difference in terms of English.

Considering operas, oratorios, sings… which one is the best? Is it easy or hard to shift between genres?

Considering operas, oratorios, sings… which one is the best? Is it easy or hard to shift between genres?

Shifting back and forth is not hard because the voice remains the same. Opera is easier because you have more time to learn your part and it is signing from forte to fortissimo, plus some mezzopiano here and there and no worries. In songs the dynamic scale is challenging and it is technically harder. Not to mention the fact that when one does liederabend it is harder to have it all in the head. I always like oratorios– sheet music in front of me, orchestra, no disruptions, no delays and the conductor in plain view, it is convenient. The liederabend is the biggest challenge.

I went to your concert in Besední dům when you were eighty. It was amazing.

I wasn’t in very good shape. I made a studio recording of the programme and I did not like it very much either. But I have learned to accept it as it is. I took a break because I underwent a hip replacement in November so I was silent for three months. Then suddenly I could not speak at all. It took a long time to heal. I have done some signing since then but I was not satisfied with my performance at all. Later I had a song evening in Velká Bíteš with Mr. Šaroun where I performed those five series. And the next day I had the sudden feeling that I was back in the game again. I used to have the same experience in the past a few times, in the opera. After a four- or six-week hiatus during the summer break it was always a lengthy process to start singing again. Getting back in shape totally required one full show. During the show, it was torture and then it came. If you are in front of an audience, it is different from rehearsals in your home. The challenge is bigger as is the stress on the neck … I don’t know. I think it is about the state of mind as well.

In your opinion, are the recordings important as documents as well as learning tools?

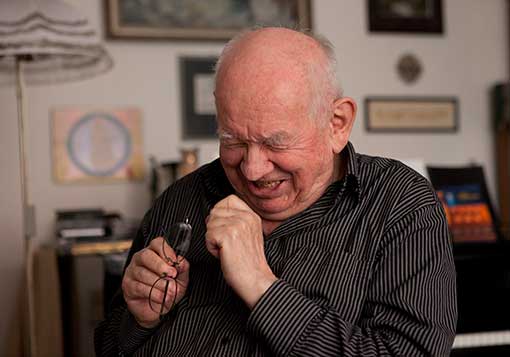

You will not find a pianist willing to do ten rehearsal sessions with you. So I will always play the recordings here and sing along with them. And these MiniDiscs and CDs are mine too. It is interesting to hear the recordings years later because it allows me to see things differently. Whenever I record something, I usually do not like it at first because the result is inconsistent with the original – very specific – idea. Every detail is very irritating and the overall impression is not good. But twenty years later I go “That is pretty good”. I have had this feeling countless times.

When the Brno municipality reduced the subsidies for its organisations, Daniel Dvořák responded that he may be forced to disband the opera ensembles. You said on TV that things like that should not be said out loud. Why?

When the Brno municipality reduced the subsidies for its organisations, Daniel Dvořák responded that he may be forced to disband the opera ensembles. You said on TV that things like that should not be said out loud. Why?

I said that this idea is out of the question. Dvořák certainly has ties to the theatre but if he suspends opera for a year and then one year from how he gets a production job, he will paint it. But you cannot just suspend an ensemble for a few months. First of all, the ensemble members will never get back together because the people have to earn money to make a living – and the salaries are bad already. It is a neverending battle because good people leave. I think it is a miracle that Pančík has managed to keep the opera ensemble together in spite of all the losses suffered. The ensemble is the most sensitive element. Young conservatory graduates with no experience and some voice join the ensemble and they have to learn from the experienced ladies and assume their style to blend in. The ensemble may change completely over twenty years but the spirit remains. It is a bit different for the orchestra. If you find good people and personalities, the orchestra can do good music within two weeks. That being said, a really good orchestra has to find its sound – and it may be a lengthy process. But there is no other way in the case of a choir. Plus I have some doubts about the soloist ensemble. It does not really exist nowadays because people arrive from all over the country or from all over the world and if they are good it won’t be noticeable. Nevertheless, I still think that in the era of the ensemble theatre – in the era of František Jílek – the ensemble had something valuable. It was not a theatre full of stars; it was a theatre with a team where its respective members know one another and cooperated. It is a valuable element, just like in the case of a hockey team. If you disrupt the harmony among players, you are killing the ensemble. And quality should matter. Without the ambition to be number one there is no point in going forward. Quality, not cost reduction, must be the number one requirement. You can save money on production costs, not staff costs. When it comes to a stage like the Janáček Theatre, there is a big difference between forty people on the stage or seventy people on the stage.

What is the position of opera in today’s world, anyway? Is there any point in showing Carmen, Prodaná nevěsta or La bohème over and over?

What is the position of opera in today’s world, anyway? Is there any point in showing Carmen, Prodaná nevěsta or La bohème over and over?

I think culture in general is going to hell anyway. People are doing fine and that want to be doing even better. But they do not need the theatre or good books. They feel like it is enough to go on a holiday in Croatia or in the Alps and watch TV shows in the evening. But in times of material trouble the attitude towards these things was much more positive and tighter. After WWII people were poor and they were doing much worse. On the other hand, TV did not exist yet. When I went to school in Brno in the 1950’s we were in the opera or at a concert in Stadion or in Besední dům every day. We did not have CD players but live music on a daily basis, which was good.

You cannot substitute first-hand experience, even today.

I rarely go anywhere because I am too old. But when I do, it is worth it. Some time ago Czech Virtuosi ask me to do a concert in Újezd u Brna, featuring Chinese violinist Esther Yoo who is the finalist of the Queen Elizabeth Competition. She has four concerts with them here and then she moves to a recording studio in London. It was amazing and I was excited to have been part of it live. The problem is that we may see opera survive in centres like NYC, London, Milan or Vienna and people in the rest of the world will only go to see filmed opera shows. As a secondary form of entertainment, why not. But I think it is important for people to be able to go to a theatre in Olomouc, let’s say. The interaction with live crowds and the ability to see certain actors is important. Brno is not doing very well, but take Opava for instance – they have five soloists there. After WWII they had Karel Berman, Jarda Horáček or Borek Jedlička. All of them were in local theatres.

Hans Hotter started in Opava before the war.

I remembered him as a singer from recordings. In 1964 I was in the opera in Vienna, I played the monk in Don Carlos and Hotter played the inquisitor. I have his signature. Once he had a show in Prague; I was about to meet with Alfréd Holeček, an occasional colleague. He said they were in the middle of the Prague Spring competition and that we can’t be seen together as it could be perceived as improper influence. We met in front of Národní dům at Vinohrady and he came with Hotter. He introduced us and I said “Maestro, I remember you from Vienna; I was the monk and you were the inquisitor” and he replied “I remember”

Could you name an unforgettable and irreplaceable colleague that will forever be missed?

Could you name an unforgettable and irreplaceable colleague that will forever be missed?

I can’t name just one because we were a team of people who remained in the theatre for years. I remember well Magda Blahušiaková and Romanová in sopranos, the unique mezzo Andulka Barová… I take them as colleagues who were absolutely reliable. I could turn around knowing that the person will be standing right there. As for tenors, I liked Vilda Přibyl and Vláďa Krejčík: we shared a dressing room for years. As for baritones, Jarda Souček was great. He was a dramatic baritone. I remember his tryouts in the old theatre building. He came in a military uniform and started singing Cortigiani, vil razza dannata and I said to myself “a good bloke”. I liked his dramatic expression. As for bassos, I had two excellent colleagues: first, Pepa Klán – amazing and beautiful round voice. Unique material. When I listen to recordings, I realise how bad we all were compared to him. And second, Honza Hladík. He was a showman, magnificent bas buffo voice. I don’t look at them from the strictly artistic point of view. They were friends, we did not compete and we were able to help another when needed. Well, it was not always like that. Some time ago as I was rearranging my tapes I found the Glagolitic Mass from Stadion with Jílek, featuring Blahušiaková, Barová, Přibyl and me. And it seems to me that Blahušiaková had the best voice colour.

I remember hearing Přibyl when I was young. He had an amazing voice…

Yes, but he was the typical “Czech tenor” after all; shiny and perfect. He did not have the volume that is normally associated with the dramatic Italians. We worked together frequently; he was particularly good as Macduff in Macbeth. A single was released with four arias from del Monaco, and I suspected he had done his homework. We argued a lot about these things and I would often tell him “This is by far the best performance. You should sing like this all the time”. And he would say “Are you crazy? My neck would have broken”. He would always tease me by standing in the back of the stage, listening and telling me “Go tell her she should stop yelling and start singing”. And I would respond “Go tell her yourself”. – “They hate me already.” – “Well, they do because of your expression which works for you, but if they tried to imitate you they would fail. So it is your fault”.

You will conclude this year’s Easter festival with a bass part in the Glagolitic Mass, standing next to Michaela Kapustová who is more than fifty years your junior. Do you have any piece of advice for her and her contemporaries, so that they can be proud to be soloists even fifty years from now?

You will conclude this year’s Easter festival with a bass part in the Glagolitic Mass, standing next to Michaela Kapustová who is more than fifty years your junior. Do you have any piece of advice for her and her contemporaries, so that they can be proud to be soloists even fifty years from now?

Nobody knows. Those are questions for women who turn 100 who either don’t know either or talk nonsense. Either way, Kapustová in particular has evidently been very busy lately so I assume she is very good. Sometimes it is painful to see how overworked the young singers seem to be and I am scared for their wellbeing. I fear unsuitable roles may hurt them, even though I know that people should be tough on themselves. In the age of ensemble theatres, a good singer joined the ensemble and the director knew right away that she was suitable for certain roles and unusable for other roles. And in the meantime she watched older colleagues nail the roles that she was declared unsuitable for. She would learn a lot this way. Sooner or later she would grow up to reach for these roles. Nowadays a young girl comes, she is good, so she is given three completely different roles in the theatres in Plzeň, Olomouc and Brno. Therefore there is no system in her professional development. I am not saying girls like her should sing less. I am saying they should be taken care of by a director who knows what he is talking about. He should know the voices and he should know how to cherish them.

There are no leaps in art, said Karel Burian.

Yes, even famous natural historians say “natura non facit saltum”. If you are to scale a high mountain, you must not rush if you don’t want to collapse along the way. You must climb in stages and not hurry.

No comment added yet..