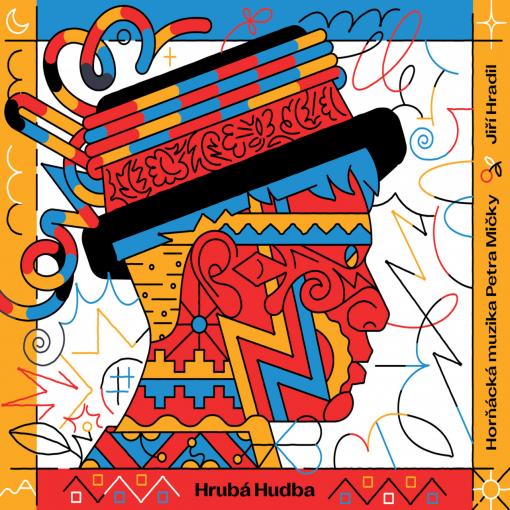

The double album Hrubá Hudba, which was jointly created by producer Jiří Hradil (Lesní zvěř, Tata Bojs, Kafka Band and others) and the Horňácká muzika band of Petr Mička, is an extraordinary musical achievement that puts together genuine Horňácko singing (the CD Hlasy starého světa [Voices of the Old World]) and folklore shifted to modern musical expression (the CD Hrubá hudba [Rough Music]). In an extensive two-part interview, we talked to the two fathers of the project, Jiří Hradil and Petr Mička, about their long-term cooperation, their path to Hrubá Hudba and finally about the double album itself and the possible continuation of the project.

Do you still remember when and where the two of you met for the first time?

JH: It was at a club at the Mahen Theatre. We were preparing the first record of the Lesní zvěř group at that time and I wanted to invite some people from the Horňácko district to join in as guests. My fellow player Miloš Rejsek knew Petr Mička because they had both studied ethnology at the Faculty of Arts. So he arranged a meeting at the Mahen Theatre, where Petr and his band played Gazdina roba live, directed by Břetislav Rychlík.

Why did you want "some people from Horňácko" in particular to appear on the album?

JH: I studied musicology, and specifically ethnomusicology was taught to us by Professor Dušan Holý, coincidentally a great Horňácko singer and populariser of Horňácko. He made us listen to some recordings and advised us to come to the Horňácké slavnosti festival if we wanted to form our own opinion. So I went to the Horňácké slavnosti for the first time in 1997 and was completely overwhelmed by something that I hadn't known until then. It was not about the fact that it was folklore, but rather about what was behind the tones and somewhere inside. So I secretly dreamed of working with this music sometime in the future, but I didn't dare say it out loud for years. I still have a lot of respect for the Horňácko people, so at the time I guessed that they wouldn't want to just mess around with someone. It wasn't until 2008 that time came and I thought I'd give it a try. So we contacted Petr and he said that they did not deal with such fusions, that they did not want to do a "Čechomor" (a renowned Czech fusion band – translator’s note) and that they did not need it for anything. I objected that Lesní zvěř [Forest Game] was something else, that it was something like alternative jazz. And I sent him the songs Hostýn, Frank Frank and Turzovka. Petr listened to them and surprisingly said that it could work…

Petr, you grew up with folklore. Do you remember the moment when you began to realise that you actually came from an exceptional environment?

PM: Hard to say. When a person grows up in it, it does seem something special to him. I've always been surrounded by folklore. We used to sing at weddings, celebrations, pig-slaughterings… When the family got together, it always ended up with singing and drinking. As children, my brother and I also sang and played in school music ensembles. The key moment was probably at high school or maybe even later, when I started studying ethnology. When I already had an insight into history, facts and contexts, I realised what kind of folk musicians had performed before us, the continuity in all that, the enormous wealth of songs we have here. Horňácko offers something extraordinary in terms of musical folklore. Today therefore I have great respect for it.

By Marek Ehrenberger

By Marek Ehrenberger

In your case what made you decide to say yes to collaboration with Jura?

PM: As a band, we only once "submerged" in an inter-genre connection with the metal band Sad Harmony, which invited us to appear in a ballad. Until then, nothing. When I listened to the samples Jura had sent me, I thought it wasn't bad and that we could give it a try. We approached the offer very carefully, but we tried not to fall for it. On the other hand, we were curious as to what it would turn out like. So we were careful, but in the end I'm glad Jura came up with that offer.

What was actually the goal of that first collaboration? To play together, side by side, face to face…?

JH: I was thinking of how to make a record with a Horňácko band for the first time. It occurred to me that it would be comfortable for them not to have to travel anywhere, but I would come to them and adapt to their time availability. They didn't have to learn anything in advance and get stressed in any way. We recorded on a Sunday morning at the municipal office in Kozojídky. We only had two pairs of headphones available, I took one myself and gave the other to Petr. The principle was that "ethnic musicians" would play their own way into something completely different, something that has no rich harmony, in order not to confuse them and not to make it gibberish, but something that has a certain hymnic nature inside. I wanted them to play as they normally play together. At the time I invented this model and later on developed it in Hrubá Hudba. That's when I made them listen to the song Hostýn. Petr, who heard it on headphones, started playing and his fellow players gradually joined in. I thus obtained about seven minutes of music. Then we gave it a second and a third try and followed up with the songs Frank Frank, Dusty Roads and Turzovka. I brought the resulting material home. I listened to the recording of Hostýn and thought that it was so good that I would leave as it was from beginning to end. I didn't have the necessary distance from it. Fortunately, there was Miloš Rejsek, who told me that if I did that, he would quit the band. Then I worked on it all night and in the end I used only about a third of the recording of the Horňácko band. But I'm very happy that the boys put it down so well in their home environment at the time.

PM: It was improvisation. We only had some fixed points, their rhythmic and harmonic features, but nothing was said, no harmony was written down. I started modulating what I picked up through headphones, and the guys joined in as is usual for our band. They played following in my footsteps, and something came out of it that Jura then used. By the way, he had sent us the songs before the recording, but I must admit that we didn't get to listen to them, let alone studying the songs before the recording session. (laughter)

JH: I think in this way we created the right concept to keep the authenticity of folk musicians as pure as possible. They play into something else, but they still play as themselves. They don't play Horňácko music directly, but the skids and tones, and the harmonies, are still there. They are strongly connected to each other, so it all fits together. Similarly, on Hrubá Hudba, they improvise into the final part of the song Hora, miłá hora [Mountain, Lovely Mountain]. It is the most beautiful film music I know. It's a sound I wouldn't have come up with as a composer. Today we already know the principle and we also use it at concerts.

Ten years have passed between the first record of Lesní zvěř we talked about and the double album Hrubá Hudba. What was happening in the meantime?

JH: After that first album, we played several joint concerts, including at the Colours of Ostrava festival. Then we were approached by director Jiří Šindar, who shot the documentary Slovácká suita based on the eponymous composition by Vítězslav Novák. He assigned each movement of the suite to a different artist for elaboration and also asked me if I would prepare something, together with the Horňácko people and with Lesní zvěř, for the fifth movement entitled V noci [In the Night]. So we did just that and it gave me the courage to create something I called Horňácké oratorium for myself. I didn't have a specific idea, I just knew that I would somehow work with the Horňácko music, that I would add some interludes and codas to it and rearrange it… It started to ripen in my head until I told the boys that I would like to have some of my hypotheses confirmed with their help. I wanted to find out if I could infiltrate something into Horňácko music, if I could fuse it with electronica and the like. I knew the line was thin and it could slip into kitsch or pompousness. But I had never heard anything like it in this country before. I'd originally had an extreme project in my head - hallucinogenic things. But the more I immersed myself in it, the clearer it became to me that it was necessary to grasp it differently, simply because similar fusions do not exist in this country at all. Horňácko is perhaps the last place in this country where such authentic folk music lives and that is why it deserves giving a try to something similar. So I gave it a try.

What did the Horňácko people say about that?

PM: When Jirka came up with the idea that we would make a record that would be directly based on Horňácko folklore, but would be shifted elsewhere by its arrangements, we actually agreed on it in the end. It only took a while before we got up the courage to do it and stepped into it.

I can imagine that it could be a problem for you to work in such a way with Horňácko folklore...

PM: Yes, I have a lot of respect for tradition and I couldn't imagine at all how far we could get with such joint creation. We were perhaps embarrassed internally, as we weren't entirely convinced, but then we said to ourselves that we liked what we had done with Lesní zvěř, and therefore, after previous experiences, we would go with it, even without actually knowing precisely what.

There are a number of possibilities of how to work on such a project. Jura, did you imagine in the first place rather a fusion of folklore with other genres, or its deconstruction?

JH: I actually used both of these methods and a lot more in addition. At first I only had a certain feeling. I didn't know exactly how I wanted to handle it, it was just clear to me that the time had come for me to start. To start with we recorded the songs Uderiła skała and Kebys była katolíčka. I then worked on the first of them for about a month, picking samples, looking for the right sounds. I put a certain beat onto the recorded song and started improvising freely into it. That improvisation then gave rise to an outro, in which I convinced myself that it really made sense. The song gave me the courage to let the boys listen to the outcome and tell them that we could follow that path. Immediately after that, I recorded Katolíčka, where the introductory choir came into my mind. I sent it to Pete and it convinced him again. After his heartfelt reaction, I already knew that we were on the right track. At the time, I had no idea what we were going to do with the other songs, but my intention was to work with each of them differently. I wanted the album to have some authorial reshaping, as well as the recording of folk music with a modern producer's approach and also a complete rearrangement of the song, recording it track by track with a metronome. By the way, when the boys first recorded with a metronome, they wanted to give it all up and quit. In the end we used it in two songs, because they got used to it quickly. Another option was an electronic psychedelic matter, which resulted in the song Všickni lidé zemrít musí [All People Must Die] with the Slovak singer Katarzia. Finally, I came up with a "Horňácko drum'n'bass", the song Około mlýna [Around the Mill]. I wanted the album to be variegated, even though Zdeněk Neusar from Frontman magazine told me that in the end it wouldn't all seem as colourful as I thought, because I couldn't rip my handwriting off from it. That's clear, but I tried to do what I could, and maybe more. When people unfamiliar with Horňácko folklore listen to the album, they may think that it is all "normal" Horňácko music, only there is something done a little differently. But when people from Horňácko listen to it, they will know immediately that everything is "different" in there.

(to be continued)

No comment added yet..